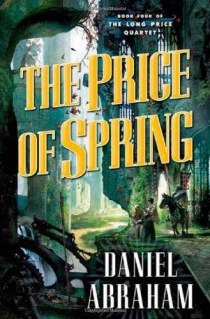

Writing this review was not easy, not because I didn’t know what to say, but rather because I didn’t exactly know how to say it. First, because talking about this series without mentioning some plot points is near to impossible, and second because when I love a book (or a series) the way I did this one, words seem to elude me… And this fourth and final book in The Long Price Quartet is more compelling than the previous ones, thanks to Mr. Abraham’s storytelling style and his writing, clear-cut and lyrical at the same time.

I’ve finally understood the meaning of the “long price” in the title: the whole story arc points at the price paid for one’s actions, and choices – and their consequences, not just for the involved individuals but for the whole world they live in. These consequences can be far-reaching, as well, given how decisions taken decades in the past can come to fruition in the present, and shape the future.

Accepting or refusing the change that comes with this realization is what makes Abraham’s characters’ tick: some still ferociously cling to the past, to the old way of doing things, therefore raining more grief on an already stricken world. Until now the danger represented by the andats (man-shaped manifestations of abstract concepts) had been clear but at the same time observed from a distance, while at the end of the previous book and in this one, the reader is treated to the full, tragic power of the creatures and the way they can influence the poets, their creators and handlers, who can in turn be shaped, or twisted, by their creations. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the andat that drives this point home is called Clarity-of-Sight, also called Blindness for his darker side.

The underlying conflict, that until now has been cultural and political, and only in the previous book turned to all-out war, becomes here a conflict of ideas, and one of personalities: it’s only fitting, from my point of view, that it’s made manifest in the struggle between Otah and Maati, the main characters. After so many years and so much history (good and bad) between them, the resolution centers on what they are in respect of each other, on how much they influenced each other in the past, and how their present actions stem from that shared past. If their origins are the same – unwanted sons of great houses, sent to the harsh school that trains poets for the binding of andats – they come to walk on different and diverging paths: one of them still tied to the past, despite the dangers of such a vision, and the other daring to dream of a different, if not necessarily better, future.

The beauty of it is that they are both right and wrong at the same time, that there is no well-defined boundary and that the very concepts of right and wrong shift according to any given situation. The horrible mistakes that are made along the way all come from the desire to do good, and their inevitable consequences plague the characters to the very end: we are constantly reminded that they are, after all, only human and as such they always do what they can, hoping for the best. That very humanity is what endeared them to me, not despite their mistakes but because of them: the story does have an epic feel, granted, but the human dimension of it is what gives it life and depth.

There is a definite feeling, in this fourth book, of the end of an era – even more definite than it was in the previous one: the sense of melancholy, the awareness that no matter what time will bring, things will never be the same anymore. Many of the characters I followed from the beginning have grown old, and the sense of loss that accompanies this natural progression only added to the poignancy of the situation, because I had to face the fact I would have to say good-bye to these characters and the world they inhabited – and it made me sad. This realization brought home the awareness of how much I had come to care for them, for better or worse, depending on their place in the story. And yet all things – all people – must come to an end because, as Abraham so poetically states in the last pages, renewal comes only through evolution: Flowers do not return in the spring, rather they are replaced. It is in this difference between returned and replaced that the price of renewal is paid.

Even recognizing the rightness of the concept, it was hard to part from this world – harder still because of the quietly emotional ending. But I also know it will be a pleasure to revisit it some time in the future.

My Rating: 9/10

What is the setting for this world?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a very unusual one: the main focus is on the Summer cities, that closely resemble feudal Japan in many of their details – the most interesting one being about “poses” that, though never fully explained, seem to be hand gestures that stress or modify the meaning of the spoken word and made me think of the different meaning that comes from voice inflection in oriental languages.

Then there are the Galts: they are more technologically oriented and use steam engines and so forth. It’s a fascinating world, and a delightfully detailed one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, Steampunk. The Saga of Recluce broke me on liking a mix of technology and fantasy. Guess I’m kind of a purest.

LikeLike

IMHO it’s not so much a mix of fantasy and steampunk, but it’s rather fantasy with a few, slight dashes of steampunk – nothing that might disturb your purist feelings 😉

And I believe you will love the Summer Cities, with their fascinatingly complex customs…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okies! Back on my list then. I’ve been on the fence with this series but I’ve seen alot of great ratings. I’ll try book one before committing to the entire series :>)

LikeLike

I look forward to hearing what you think about it! I liked his style so much that I have his other series “The Dagger and the Coin” lined up: it’s a more “classic” fantasy series and it’s on the fourth (and next to last, I believe) book. If I like it, I will not have to wait too long for the conclusion….

LikeLike