I received this novel from Orbit Books through NetGalley, in exchange for an honest review: my thanks to both of them for this opportunity.

It’s once again time for an unpopular opinion on a book that seems to mostly receive high accolades: I requested Nophek Gloss because of its promise of a space-faring adventure and revenge quest (I can never resist a good vengeance story), but found myself struggling to move forward – I set it aside twice, hoping that some distance might foster a different perspective, but once I reached the 58% mark and realized that I was forcing myself to read, I knew I had to admit defeat and walk away from it.

Nophek Gloss starts with an adrenaline-infused inciting incident: 14 year old Caiden and his family live on what looks like an artificial environment, raising cattle; his knowledge of life is quite limited, yet he feels the need to always question rules that have been there for a long time. A devastating epidemic, however, kills the cattle that the colonists are tending and their overseers load all the people on a huge transport with a vague promise of relocation to a new facility. What follows is instead the devastating, bloody end of all that Caiden knew and loved, so that the only thing fueling his will to survive is the burning need to find the ones responsible for his loss and make them pay.

I opened this book with great expectations – maybe too great – and at first it appeared to be all that I was looking forward to, but just as the story reached its first turning point for Caiden (i.e. his encounter with a diverse group of mercenaries who took him in, offering him the chance both to survive and to learn the skills he would need to reach his goal) everything became chaotic and I began to lose my grip on the narrative.

The universe in which Nophek Gloss is set is rather a conglomeration of universes whose borders can be traversed, each one possessing unique qualities and endless life forms: the problem for me is that this kaleidoscope of worlds, aliens and technologies is offered in what to me amounted to a massive sensory overload – there is a LOT of it, all thrown at the reader with hardly any time to process it before more details are added to an already confused and confusing tapestry. I don’t mind having to work my way through a story, visualizing or extrapolating what the author is keeping on the sidelines, but here most of it looks like a jumble of terms with no rhyme or reason to it – remember the worst moments of Star Trek’s so-called technobabble? Something like: “reroute the pre-ignition plasma from the impulse deck down to the auxiliary intake”… Well, a good portion of this novel made me feel that way, and it bothered me because it made little or no sense and kept me from forming a mental image of the world the author was trying to show.

Caiden is the other almost insurmountable problem I faced: granted, he’s a teenager and he undergoes a horribly traumatic experience, so it’s understandable that he would suffer from PTSD and survivor’s guilt and would be consumed by the need to exact his revenge on the ones responsible for the situation, but there is no space for anything else in Caiden’s psychological makeup, and that makes it very difficult to see the humanity – if any – behind that huge wall of mindless hate. And I don’t use the word ‘mindless’ carelessly, because Caiden never fails to bodily launch himself against those offenders as soon as he sees one: it doesn’t matter that his new friends advise caution, or that he keeps entering a fight he’s not equipped to win, because as soon as he sets his sights on them he charges like the proverbial bull shown the red cape. And he does that repeatedly, as if every encounter were followed by a complete memory erasure that made him forget past experiences, or – worse – as if he were unwilling to learn from his mistakes.

Worse, the 14 year old accepts a procedure that bestows six years of physical growth on him, together with the sum of knowledge his previously secluded life could not provide: this could have been an interesting way of bringing him to adulthood in a brief span of time, narratively speaking, but keeping his reactions those of a teenager – an unthinking teenager at that – makes that a moot point, because what use is a grown body when your emotions remain those of a child? Not to mention that this choice did little to endear Caiden’s character to me…

When all is said and done, I guess it all comes to personal preferences rather than authorial skills: Nophek Gloss is certainly an ambitious, imaginative story with a rich background, but sadly it’s not the kind of story I can bring myself to enjoy.

Some time ago, a friend told me about the In Death series written by Nora Roberts under the pseudonym of J.D. Robb, and I decided to give it a try, but unfortunately the story did not work for me: I found that the author favored some telling over showing and often indulged in sudden changes of p.o.v., a technique I don’t exactly approve of.

Some time ago, a friend told me about the In Death series written by Nora Roberts under the pseudonym of J.D. Robb, and I decided to give it a try, but unfortunately the story did not work for me: I found that the author favored some telling over showing and often indulged in sudden changes of p.o.v., a technique I don’t exactly approve of. If someone had told me that I would not be able to finish a book by Alastair Reynolds, I would never have believed them: he’s one of my favorite SF authors, and I’ve always enjoyed what I read so far, so when I learned of this new novel I dived straight for it, only to be profoundly disappointed.

If someone had told me that I would not be able to finish a book by Alastair Reynolds, I would never have believed them: he’s one of my favorite SF authors, and I’ve always enjoyed what I read so far, so when I learned of this new novel I dived straight for it, only to be profoundly disappointed.

When a book starts as strongly as this one did, with a story that’s attention-grabbing from page one, the disappointment for its failed promises hurts twice as much: this is what happened to me with The Unnoticeables, whose narrative arc… imploded (for want of a better word) two thirds of the way in.

When a book starts as strongly as this one did, with a story that’s attention-grabbing from page one, the disappointment for its failed promises hurts twice as much: this is what happened to me with The Unnoticeables, whose narrative arc… imploded (for want of a better word) two thirds of the way in.

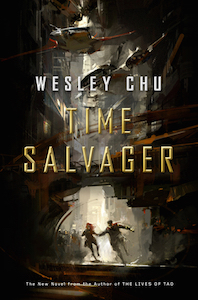

Experience should have taught me by now there is no guarantee that a highly acclaimed book might automatically be right for me – and yet there are times when widespread praise breeds high expectations, so that when a book falls short of those expectations, I’m bitterly disappointed. Time Salvager is a case in point.

Experience should have taught me by now there is no guarantee that a highly acclaimed book might automatically be right for me – and yet there are times when widespread praise breeds high expectations, so that when a book falls short of those expectations, I’m bitterly disappointed. Time Salvager is a case in point.

You must be logged in to post a comment.